This past January, an exhibit at the National Gallery of Bangkok honored the Scottish photographer John Thomson (1837-1921). For those who missed the show, or wish to enjoy its splendid images at leisure, the Thammasat University Library’s new acquisition, Siam Through the Lens of John Thomson, 1865-66, is ideal. It is written by the Thai photographer Paisarn Piemmettawat and translated by the curator of the exhibit, Mom Rajawongse Narisa Chakrabongse, a publisher, author, and environmental activist. When Thomson came to Siam, he naturally sought to capture images of the most distinguished people of the day, including King Mongkut (King Rama IV) and King Chulalongkorn (King Rama V). The exhibit of 60 photographs marked the 150th anniversary of his visit, as well as the fifth cycle of HRH Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, who has visited and studied the collection of photos in their permanent home, London’s Wellcome Collection.

This extraordinary resource was gathered by Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome (1853-1936), a pharmacist and collector who cofounded the noted pharmaceutical company, Burroughs Wellcome & Co. The Wellcome Collection specializes in objects relating to medicine, health, anthropology, and related subjects. Today over two million items are housed at the Wellcome Collection. In a generous spirit of sharing knowledge and beauty, images of many of these items are readily available for public use on Wikimedia Commons. This is unlike many other public and private collections, which do not allow comparable public access to the treasures they own. In addition to collections of artworks and objects, the Wellcome Collection also owns such books as John Thomson: the Early Years: In Search of the Orient, a useful biographical study published last year in Bangkok which is not currently in the TU Libraries. It is available by interlibrary loan, and with Siam through the lens of John Thomson, 1865-66, explains how Thomson captured fascinating images of the Royal Barge Anantanakkharat as well as many scenic images of Bangkok.

Many of Thomson’s photos were taken around the area where the National Gallery is located, although naturally appearances have changed in the past century-and-a-half. Thomson was the first photographer to be allowed into the Grand Palace. Thomson experienced some unusual adventures in the Kingdom. After traveling along the Chao Phraya River to Ayutthaya, he was charged by a water buffalo which he was trying to photograph. In his book The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China, and China or, Ten years’ Travels, Adventures, and Residence Abroad, Thomson wrote:

I arrived in Bangkok on September 28, 1865, and steamed up through the floating city in the dimness of the early morning light. It is a place which other travellers have already described; yet, as I spent some time there, the reader will pardon me if I give my own impressions of what struck me as its most remarkable features. When I use the term floating city, I mean to say that the dwellings of the people are for the most part afloat on rafts, and it is impossible at first sight to determine where land begins, and where it ends. Before proceeding to describe these aquatic abodes and their amphibious-looking inhabitants, I must remind the reader that my first ideas as to the splendor of this oriental city were gathered at dawn, when I was gazing upon the towers and roofs of more than half a hundred temples, standing each of them in its own consecrated ground. I inquired of what material these strange edifices were made, for their towers seemed ablaze as with jewels, and sparkled like refined gold.

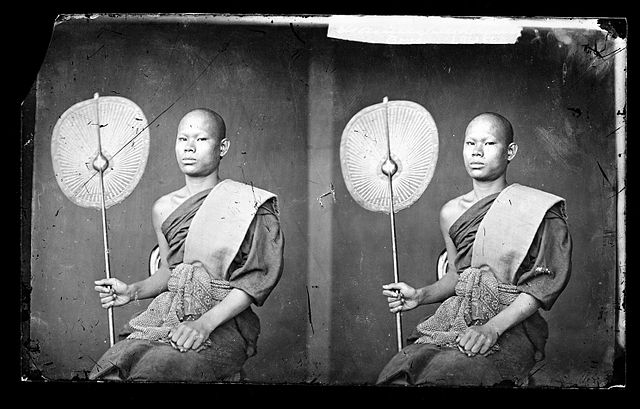

While impressed by the learning and religious observance of Rama IV, as well as his mastery of the English language, Thomson also took time to get to know humble people of Bangkok. Among these was an impoverished Buddhist monk, whom he described in his memoir with a fine eye for detail, noting that the monk created art for his temple based on photographs taken by Thomson:

One priest I knew well, and was in the habit of visiting, divided his attention between the pursuits of literature, perfect self-absorption, and the taming of a colony of white rats and mice. This devotee s cell was lit by a small window, and screened by a faded filthy Buddhist robe, which allowed a feeble streak of sunshine to struggle into the cold interior. At one end of the apartment there was a simple platform of wood, covered by a straw mat. On this he slept at night; on this he sat, wrapped in silent meditation, brooding over his sins by day. Above, in a dark corner, was a cage where his little favorites were busily at work upon a tread-mill. These rats and mice he tended with the most peculiar care, because their white skins have a sacred significance for the Buddhists, and each tiny body may contain, as is supposed, the spirit of some Buddha of the future. A number of sacred books on a shelf, one or two bowls of brass or coarse earthenware, and a mat on the clay floor, completed the furniture of the dwelling. This recluse had a taste for drawing, and was occupied in decorating the inner wall of a royal Wat with objects of Buddhist mythology. The cartoons produced were remarkable for gracefulness of outline, richness of coloring, and strange imagery; the faces of several he copied from photographs, and other pictures which I supplied to him; and he would experiment sometimes with my water-colors, though, on the whole he preferred his own, or those of Chinese make.

Thomson was generally understanding of cultural differences, as when he described needlework done by noble ladies:

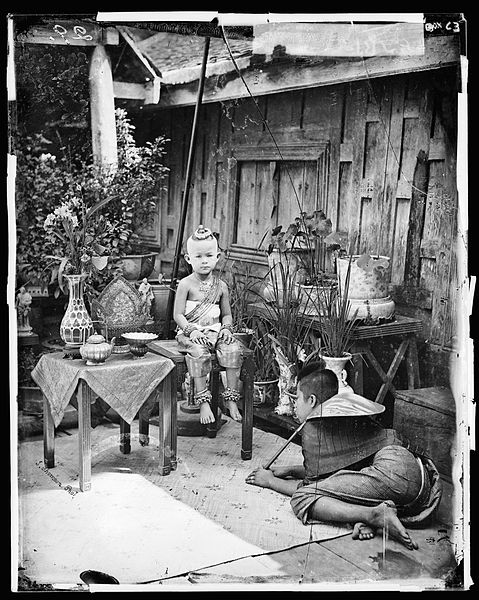

They were usually engaged in embroidery, and their needlework displayed both beauty of design and skill. I thought it a pity to see them smoking cigarettes, or chewing betel-nuts, the teeth blackened with the incrustation, and their mouths disfigured with blood-red juice; they had also perforce a nasty habit of spitting into golden vases which their slaves held up dutifully for the purpose. As for the children, they seemed to be born with a cigarette in their mouths. I have actually seen a child leave its mother’s breast to have a smoke.

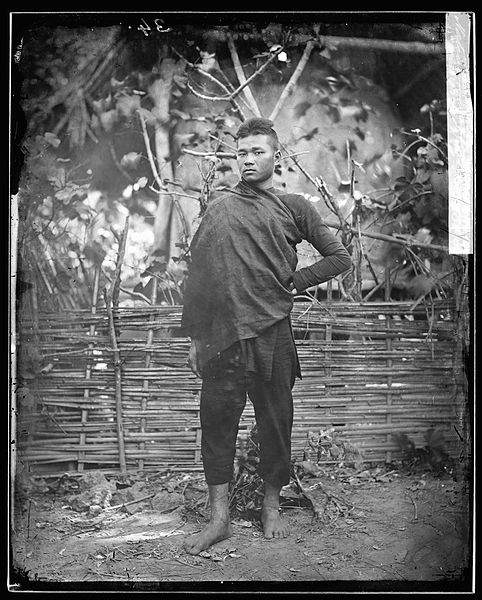

Thomson visited and photographed other parts of Asia as well, including China, Malaya, and Sumatra. He stayed in Siam for over a year, before going to Angkor, Phnom Penh, and Hong Kong. In 1921, Henry Wellcome purchased Thomson’s original glass plate negatives, from which modern prints have been made, including those in the traveling exhibit. 660 of the original negatives have been restored and digitized. Thomson’s photographs are of unique beauty, but also reveal a fine eye for the details of everyday life. In London, he was well-known as a photographer of street scenes. Even when he was in less familiar territory for him, Thomson managed to capture some essential aspects of Bangkok life. Some of the non-royal people he photographed remain unidentified today.

How Thomson did it.

Thomson was not just a traveling photographer. He also co-founded a manufacturing business to provide marine chronometers as well as optical and nautical instruments to customers. When in Singapore, he opened a photo studio, realizing that European merchants passing through the region would be willing to pay to have their images captured in such exotic settings. With the care of a mid-Victorian naturalist, he sought to understood the countries he lived in. In October 1864, a cyclone of historic destructive power hit Calcutta, India, killing about 60,000 people. Before the debris was cleared away, Thomson had already planned a visit to Ceylon and India to photograph the destruction. After this grim voyage, he sold his photo studio in Singapore and moved to Siam. He would later take some of the first photographs of Angkor Wat. More than just valuable early images, Thomson managed to create pictures of high artistic value. He did so despite the challenges of frequently uncomfortable travel conditions and a heavy wooden camera with large glass plates and explosive chemicals. After moving back to London, he opened a studio where he photographed British royalty and socialites. In 1881, Queen Victoria appointed him photographer to the British Royal Family.

Thomson’s originality.

As the website of the touring exhibit Through the Lens of John Thomson explains:

Unlike most photographers working in the Far East at that time, Thomson was not a government official, nor a missionary. He was a professional photographer who was fascinated by Asia and its people. Thomson possessed an open mind and was sensitive to the lives and surroundings of his subjects.

(all images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)